The Federation of Post-Secondary Educators is a longtime supporter of the work of CoDevelopment Canada. CoDevelopment Canada is a BC-based NGO that works for social change and global education in the Americas. A wonderful strength of CoDev is that it has an existing network of people to contact and partner groups to work with. They are on the ground, helping existing worker advocates and organizations help workers. The projects CoDev helps with are very effective and very cost efficient.

In 2016, CoDev offered a unique opportunity for FPSE and for other unions to send representatives to Central America to see, first hand, the work our donations support. We spent 4 days in each of Managua, Nicaragua and San Pedro Sula, Honduras. Kirsten Daub, Executive Director of CoDev was our guide, translator, and organizer.

Participants:

Leslie Molnar – FPSE, Eliza Gardiner – FPSE, Alexandra Phillips – FPSE, Andie Chenier – CUPE, Anita Bardel – HAS, Silke Allard – BCGEU, Jessica Smith – BCGEU, Anita Sullivan – BCGEU, Minerva Porelle – CUPE, Jennifer Fleur – HEU

May 22

Eight of us met at 4:45 AM at YVR. We met two more participants, who flew in from eastern Canada in Houston, Texas. The last member of our group, Jessica, was already traveling around Nicaragua the week before our tour, so she joined us at our hotel.

We were picked up by a driver from MEC and taken to our hotel.

The hotel we stayed in had its own charm. It was gated, with a guard, and the room keys were huge metal things which you left at the front desk. It had a total of 11 rooms. Each of our rooms had two twin beds. The showers worked, the toilets worked most of the time, and we had wifi. There was a common lobby area where we ate breakfast and there was a small pool out back. It was hot and it was humid! We were all exhausted so went to bed early.

May 23

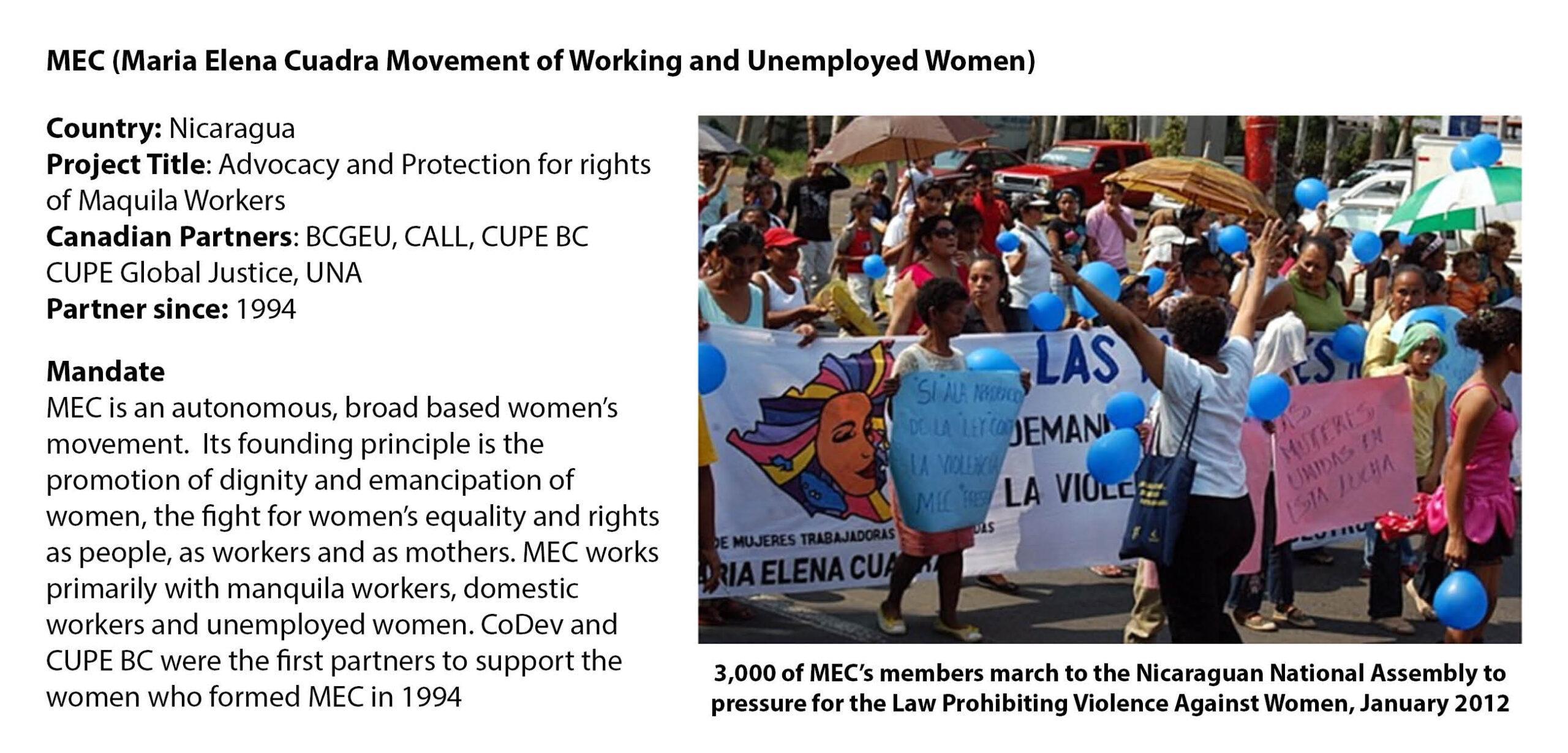

CoDev’s partner in Nicaragua is MEC – Maria Elena Cuadra Movement of Working and Unemployed Women. They fight for women’s equality for their rights as “people, workers, and mothers”.

We were picked up in a mini bus and driven to the MEC “offices” at 8 AM.

We were picked up in a mini bus and driven to the MEC “offices” at 8 AM.

The first presentation was about Nicaragua. We learned the population of Nicaragua is about 6 million and it is a very young population. Average age is in the early 20’s. We learned about the government set up and the free trade zones. Labour is very cheap here. A lot of people make a living by just selling things – you see those people everywhere – on the sidewalk, at traffic intersections, etc. Even though there are a lot of people who live in poverty, since there is coffee and other exports, Nicaragua itself is considered a middle-income country so is only eligible for loans, not grants, for foreign aid. Apparently, about 12 families control 90% of the wealth in Nicaragua.

We learned that the unions are not doing that well for labour rights and women’s rights in particular. MEC helps to fill that gap.

The presenter talked about some good programming. For example, there is a program in rural areas where women can get chickens, a cow, or a pig. These animals become the women’s possessions, not their husbands. The women can feed their families with milk and eggs from the cow and the chickens and can sell the piglets for money. They must give a piglet back to the program as payment.

A disturbing thing we learned was that all abortions, including therapeutic abortions, are illegal. (This is also true in Honduras.) Girls who are 11 and 12 years old, who are pregnant because of rape, have to have their babies. We learned the bus transportation is very cheap because it is subsidized, but it is subsidized for the entire population – rich and poor. Our presenter strongly believed in targeted programming.

The MEC staff focus on women’s labour rights. They have a lot of volunteer women organizers, and they have a few lawyers who help women with legal issues and forms. The MEC leader, Sandra, is an amazing force of personality. She has been beaten and threatened with jail for her work, standing up for women’s rights.

The women train each other. They will often have workshops on the weekends and call it something else (like something to do with cooking), so the women are allowed to go.

The women train each other. They will often have workshops on the weekends and call it something else (like something to do with cooking), so the women are allowed to go.

In the afternoon, we met with people from the media. These particular people are very supportive of MEC and are part of small radio stations or newspapers. Radio, not TV, is the main source of news for most people. They pride themselves on spreading the news about the successes. As one person told us: “If a chicken lays an egg, and no one squawks about it, no one knows about the egg”. He called the media “the squawkers”.

Health and safety is a huge issue here. As are low wages, no benefits, etc. The factories are profitable for owners and managers, but the workers don’t see the profit. Often women stay home to look after children but then they have no income. Looking after children has no economic value.

Before we went out for dinner on the first day, Jennifer and I ventured out to find a “pharmacy”. Her sandals weren’t comfortable, so she was looking for moleskin. I forgot hair conditioner. Luckily, Jen speaks Spanish because every block it seemed, we were pointed a different direction. I didn’t feel unsafe (although I probably would have if I were alone). When we found the pharmacy, it (like other stores) has metal bars in front. You don’t actually go in the store. You point to the item you want, and the salesperson will show it to you and tell you the price, etc. Your money then goes in a slot and the merchandise is passed out through the same slot. We saw this same set up in several stores later in the trip.

Monday evening, we went to the park near the lake, walked through some of the Trees of Life, saw a museum which was 4 replica houses of famous people from Nicaragua, including Nicaragua’s revolutionary leader Augusto Sandino.

The “Trees of Life” are impressive to look at. They are 17 meters tall each, and there are 134 of them in total. Designed by Rosario Murillo, the wife of Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega and the Nicaraguan government’s official spokeswoman, the trees of life are a conspicuous example of the first lady’s far-reaching influence. Local media estimate that the trees have cost Nicaragua upwards of $3.3 million to construct and an additional $1.1 million annually in electricity bills.

May 24

May 24

Another early start to the day. We met in the lobby at 5:15 AM to board our bus and drove to a factory entrance area. About 40,000 people would pass through the gates here on their way to work (several different factories will share the same gate). We worked alongside MEC and gave out their pamphlets on worker rights. So many people. Most of the workers passing through the gates were young (both male and female), had taken the time to dress as nicely as they could, and were preparing for long shifts at their factory work. There were so many people, it was like watching snowflakes coming at me. Along the way, vendors sold food (for breakfast now, for lunch later), and pain medications. Addictions to certain medications and drugs is a national problem.

We returned to the hotel and it was barely 8 AM. It was hot (it was 44 degrees Celsius by 10 AM) and humid (about 80%). We ate breakfast then were back on the bus to go to MEC, this time to hear the stories of a panel of women. We heard about their work related sicknesses and injuries, about how many of them could no longer work, and could no longer do day to day tasks, like lift their arms over their heads to wash their hair, or wash their own clothes.

We returned to the hotel and it was barely 8 AM. It was hot (it was 44 degrees Celsius by 10 AM) and humid (about 80%). We ate breakfast then were back on the bus to go to MEC, this time to hear the stories of a panel of women. We heard about their work related sicknesses and injuries, about how many of them could no longer work, and could no longer do day to day tasks, like lift their arms over their heads to wash their hair, or wash their own clothes.

When the workers complain of illnesses or injuries, they will see a factory doctor, but the doctors won’t diagnose these as work related. They always find another cause.

Some factories are worse than others. Some make the workers wear Depends, so they don’t take bathroom breaks. Some don’t provide any safety equipment. None of the factories we heard about accommodate for ergonomics or repetitive stress injuries. Work stations are not adjustable.

We went to another factory later in the day and distributed 3000 more pamphlets. The workers came out over a time span of a couple of hours. They all go in to work at the same time, but the workers leave at different times – they can’t leave until their quotas are full.

May 25

We didn’t have to be on the bus until 8:45 AM – nice start to the day!! We were driven to a factory which allows MEC to talk to the administrators. We were told we could ask questions, but we were aware we were guests in this factory and didn’t want to ask anything which would block MEC’s future access.

The particular factory we saw produces clothes for Dockers, Levi, and Dickies (for sure). Those were the labels we saw.

First, we met with the HR manager, in an air-conditioned conference room overlooking the factory floor. The manager explained about “worker rights”. Workers get breaks, 2 soda pops per day, and water. Work week is six 8-hour shifts. There is a “minimum wage” but there are quotes and “incentive” payments. Highest wages are for cutting and pressing. There are opportunities for advancement if the worker wants them but often, they have to go for training and, unless they can get a “scholarship” from the company, this is not possible. So, many workers do the same job, day after day, year after year. Young workers are working even faster (because they are still physically able to) to get the extra pay for exceeding the quota.

The HR manager seemed like he genuinely wanted to do the best he could, but he is limited in what he can do. There is not enough money to air condition the work space – just the admin offices. He talked about the fact that nursing mothers can come to work late or leave early for 4 months, without losing pay. He talked about the loan sharks who come every Friday to collect from workers who have borrowed from them. The company has a loan system where they charge less interest (but do charge interest) then use that revenue to fund “scholarships”.

Then, the Manager came in. He is Cuban American. He talks about doing social good but says if people get something for nothing, they will become lazy. He blames a lot on the American welfare system. He talks of hope and kindness, yet he wears an Apple Watch while his workers’ wages were recently cut in half. He says to them “if you can find another job, then good for you. Otherwise, this is the wage now.”

Because of the cheap labour in places like Bangladesh, companies like Levi now pay less to have a pair of pants made. For example, they used to pay about $4 per pair of pants, but now it is less than $2. The company used to be able to buy fabric at a good deal – now they have to buy at least half from American suppliers who are more expensive. Even so, a pair of pants (like Dockers) which retails for about $80 will generate $9 in total from the corporation (pay for labour, materials, admin, shipping, etc.). He says his factory does not lift people out of poverty, rather lifts then from despair to poverty. The average wage is about $200 per month, less than $8 per day.

The owner came across to us as arrogant, but he believes he is socialist. Later in the day, he sent us all emails about “love” (we all deleted these).

The company has lost a lot of contracts to Asia or factories in Bangladesh, so have reduced their workforce from 1800 to 1200 workers. Boycotting certain corporations is not going to help these people. The best thing we could do is get any Canadian company (or company who sells in Canada) to have to pay the factories more for the labour.

Next, we went onto the factory floor. I took pictures but they don’t capture the heat or the noise. None of the work stations were adjustable. Workers do the same job, over and over. For example, one person just sewed on one particular belt loop. Another person just measured and marked where the belt loops would go. One person sewed zippers. Another person sewed a particular seam. Everyone was in a hurry and working as fast as they could. Each step in the process depended on the previous step also working quickly.

At the beginning of the process, long bolts of fabric are rolled out into many layers. The patterns are put on the “cutters” cut many thicknesses of the same piece. Pieces are numbered and go to the various sewing stations. The end process is pressing, and the heat is like an inferno. Only men were doing the cutting and the pressing. Only a few workers were wearing any protection. The pressers did wear leather gloves so their hands wouldn’t burn. I will never look at a pair of pants the same way again.

We were there for over 4 hours. The heat, noise, smells, feel, etc. of the factory was overwhelming after just 4 hours – imagine 8 to 12 hours days, 6 days per week.

Next, we went for lunch (at about 3 PM) and were able to try more of the local type food. which centers around rice and beans (I liked it). We had some free time next so were taken to a local market to shop. The market was mostly full of very touristy trinkets (I am not a shopper). We got back to the hotel by about 8 PM, had beer and chips by the pool and went to bed early for our 4:30 AM start the next day.

May 26

May 26

Early start – got driven to the airport, said goodbye to our driver (who had been wonderful!) and waited for two hours at the airport. No one looked at my tourist visa or took my customs declaration. I was able to bring my full water bottle through security.

We flew Copa Airlines to Panama City (making me have that Barry Manilow song in my head all day). To my surprise, we had been upgraded to business class. Full reclining seats, a warm breakfast, a blanket – it was a lovely flight. And, I could see the Panama Canal from the air as we flew in.

Two hours in the Panama City airport, then another first-class flight to Honduras. Things feel different in Honduras. I got pulled aside at customs. They took my passport and made me wait while they made a long telephone call. Both hands were fingerprinted. Finally, I was through and met up with the rest of the group. I do admit, I was nervous, thinking about the stories of crime and violence I had heard about Honduras. Kirsten reassured me we would be well taken care of. After we landed and got to the hotel, we have some free time before a meeting with the partner group at 5 PM.

The hotel was functional but not charming like our little hotel in Managua. Weirdly, it had a Scandinavian theme in its décor (from about the 1950’s) and had an American style café as its restaurant. We ate there a lot, as we were not allowed to wander the streets after nightfall.

San Pedro Sula is a city of about 1.4 million people. It was the “homicide capital of the world” until early this year when Caracas, Venezuela, surpassed it. As I am sure most of you know, there was a military coup in 2009. You see people carrying guns in the street. You see gun barrels sticking out of the windows of vehicles. But you also see people who look just like ordinary people, getting on with their lives. Personally, I didn’t feel the same sense of hope I felt when we were out and about in Nacaragua. People were poor but not despairing. In Honduras, in lots of places there was a feeling of fear or hopelessness.

San Pedro Sula is a city of about 1.4 million people. It was the “homicide capital of the world” until early this year when Caracas, Venezuela, surpassed it. As I am sure most of you know, there was a military coup in 2009. You see people carrying guns in the street. You see gun barrels sticking out of the windows of vehicles. But you also see people who look just like ordinary people, getting on with their lives. Personally, I didn’t feel the same sense of hope I felt when we were out and about in Nacaragua. People were poor but not despairing. In Honduras, in lots of places there was a feeling of fear or hopelessness.

Our partner group in Honduras is CODEMUH. It is also a women’s group which works hard for human rights, worker rights, and health and safety. One of CODEMUH’s successes is its work with a Mexican doctor, Dr. Luis Perez, an expert in maquila health and safety. Together, they have documented the link between many musculoskeletal injuries and the repetitive, fast pace of the maquila industry. Honduran workers are able to apply for workplace accommodations and disability pensions. At the time we were there, CODEMUH was helping a worker named Lillian, who had been fired for making a health and safety claim and for not agreeing to be bought out for a small payout. After we returned to Canada, we heard that Lillian was employed again and had received a workplace accommodation.

CODEMUH is also very active politically, lobbying for ergonomic assessments, a review of the 12-hour work day, and minimum salaries. They are active in the campaign against femicides (an average of 51 females are killed each month, many of these on their way to work in the early morning hours). They also are forging ties with the union movement in the country, although many of the unions are thought to be corrupt and controlled by gangs.

On the evening of May 26, we met with workers from CODEMUH, led by Maria Luisa. If you were on PC last November, Maria Luisa came and spoke to us about the plight on the worker in Honduras. Kirsten Daub accompanied her and translated for her. In this first meeting, they told us about the work they do, they told us about Lillian, and they highlighted a particular Canadian company, Gildan Industries, who has factories in Honduras and does not treat their workers well.

May 27

Most of the group went with members of CODEMUH to a public demonstration for the International Day for Women’s Health. (I did not attend. I was feeling a little freaked out by my experience at customs. Having put “tourism” for my reason for being in the country, I was reluctant to be part of a political demonstration, if something went amiss. But my worries were groundless. Everything was fine.)

After that, we went on our shuttle bus to CODEMUH’s offices in Choloma. The office was really a small house-like building with a living room (meeting room), kitchen, and a couple of small rooms used as offices. Maria Luisa was busy writing up a grant application. The room was filled with women, some with their children, all of whom wanted to tell us their stories.

These women learn from each other how to stand up for their rights in the workplace. They learn how to approach other women, to try and let them know about their rights. They help workers make complaints. When a worker (male or female) reports a workplace injury, the first thing the company wants to do is get rid of that worker. The people from CODEMUH try to help the workers keep their job and instead get a workplace accommodation. They also learn strategies to cope with violence – both violence in the workplace and domestic violence.

These women learn from each other how to stand up for their rights in the workplace. They learn how to approach other women, to try and let them know about their rights. They help workers make complaints. When a worker (male or female) reports a workplace injury, the first thing the company wants to do is get rid of that worker. The people from CODEMUH try to help the workers keep their job and instead get a workplace accommodation. They also learn strategies to cope with violence – both violence in the workplace and domestic violence.

We had lunch in a restaurant in CODEMUH which reminds one of a fast food place. I’m not complaining about the food. Rice, beans, cheese – it’s all good. This particular place was in a mini-mall type of structure. There were two workers, trying to put an air-conditioning unit up on the roof. A very tall, not that sturdy ladder was leaning against the building. One worker was sitting on the roof, near the top of the ladder, his feet hanging over the edge of the building, with a rope in his hands. The rope was attached to the air-conditioning unit which was balanced on the head of the other worker. The person with the air conditioner on his head would take a step up the ladder, and the person on the roof would take up the slack in the rope. That is how they brought the unit up to the roof. Everywhere, there were examples of safety hazards. Loads weren’t properly tied down (if they were tied at all), hazards weren’t marked, etc.

Later that day, we drove to a different city, El Progresso, to meet with the leaders of the SitraStar union.

Later that day, we drove to a different city, El Progresso, to meet with the leaders of the SitraStar union.

As far as unions go, apparently this one actually tries to get some improvements for its workers (instead of the accepted role of just accepting bribes and signing any collective agreement). The “office” was an area with bars, and the door was kept bolted. The union leaders were two young men. They really did seem like they had hopes and good intentions. They struggle just trying to keep the jobs the workers have – factory owners regularly reduce the workforce. But death threats (and other types of threats) are a part of their daily lives. We talked to these leaders for a couple of hours and again, heard their stories. They were very concerned with negotiating how workers got paid. Some are on quotas. Some factories make workers be in “teams”, so your salary depends on your team’s quota. Always there is a push to increase the quotas and decrease the daily wage. Everyone had a story to tell. But soon, we were headed back to the hotel because you don’t want to be out on the streets in San Pedro Sula after dark.

May 28

Another day of talking with workers from the Maquila sector. This morning, we talked particularly to women who worked for Gildan (the Canadian company). Again, the repetitive motions, the lack of adjustment in work stations, the dangers in walking to work, the push from the company to lay off workers who are 30 and broken because there are hundreds of 18-year-olds waiting at the factory gates, wanting jobs. Many women are bitter – their health and their youth have been stolen from them. Since we are Canadians, they want us to do something about this Canadian company.

In the afternoon, we drove to Villanueva, where CODEMUH has a small property with a small house. This is a gathering place for women, for workers, for labour activists. Decorations still hang from trees – they celebrated a child’s birthday here last and there are the remains of a piñata. We are there, workers from CODEMUH are there, and other women have been invited. Many brought their children with them. Some women are there for the first time.

In the afternoon, we drove to Villanueva, where CODEMUH has a small property with a small house. This is a gathering place for women, for workers, for labour activists. Decorations still hang from trees – they celebrated a child’s birthday here last and there are the remains of a piñata. We are there, workers from CODEMUH are there, and other women have been invited. Many brought their children with them. Some women are there for the first time.

We sit on chairs in a huge circle on the grounds outside. It is hot and there is not much shade. One woman passes out from the heat so there is a flurry of activity while she is tended to. Maria Luisa begins to speak. She tells the story of their successes and encourages the women to stand up for their rights. Then she invites other women to speak. 5 or 6 women tell their stories. They are young, they all have injuries, their employers are trying to get rid of them. But these women are brave. They have stood up for their rights. They have argued with their supervisors. And they are willing to help other workers learn how to do this.

We sit on chairs in a huge circle on the grounds outside. It is hot and there is not much shade. One woman passes out from the heat so there is a flurry of activity while she is tended to. Maria Luisa begins to speak. She tells the story of their successes and encourages the women to stand up for their rights. Then she invites other women to speak. 5 or 6 women tell their stories. They are young, they all have injuries, their employers are trying to get rid of them. But these women are brave. They have stood up for their rights. They have argued with their supervisors. And they are willing to help other workers learn how to do this.

Often, husbands will not permit their wives to come to this sort of activity, so these workshops are conducted under the guise of making jewelry or chocolate. They actually do these things and sell the products. Then, the husbands let them come because they bring home a little money. We all buy their crafts. Kirsten and Jennifer are kept really busy translating for us because, one on one, everyone wants to tell us their story.

May 29

Our scheduled meeting for the morning got cancelled so we left early, drove north, and spent the day at the beach at Tela. I’m really glad we did because I got to see much nicer parts of the country than just the concrete of San Pedro Sula. The land is hot and dry still – the rains should come soon but are late. There is concern about the vegetation. Much of the natural landscape has been replaced with acres and acres of palm trees (for the oil). There is no ground cover around these planted trees, so soil erosion is a real problem during the rains.

Kirsten took us to a beach where a family from Honduras might go. We rented a table with some shade cover for the day. We were also able to rent a room in the small motel there, so we had a bathroom and a place to change for the day. Local children were fascinated by us but lost interest once it was clear we weren’t going to give them any more money, buy any more food, and we were out of the potato chips we had brought.

Kirsten took us to a beach where a family from Honduras might go. We rented a table with some shade cover for the day. We were also able to rent a room in the small motel there, so we had a bathroom and a place to change for the day. Local children were fascinated by us but lost interest once it was clear we weren’t going to give them any more money, buy any more food, and we were out of the potato chips we had brought.

We took turns sitting with and watching our stuff and playing in the waves. I lost my sunglasses in a particularly big wave which sent me for a tumble. It was a great way to destress. Anita (from BCGEU) had brought some snorkeling equipment with her but it wasn’t the type of beach that is good for snorkeling (no reef and powerful waves). Again, the local children were fascinated by the mask, snorkel and fins and Anita gave the set to a family there.

In closing – it was a wonderful, different, perspective changing experience and I am so grateful to FPSE for providing this opportunity for me. There were 11 of us women who spent all our time together for 9 consecutive days. Everyone got along so well. Everyone supported the other people in the group. We all had times where the heat made us feel faint, where the food wreaked havoc with our digestive systems, when our roommate had snored so we were tired and cranky, when our feet were swollen, and we were tired of being in small, hot rooms with more than 30 people generating even more body heat. But we were all kind and supportive. I made some wonderful new friends.

We all know how privileged we are to live in Canada. In FPSE, we have cared about human rights and international solidarity for years now. Let’s not get complacent. Let’s think about the clothes and the products we buy, think about where they were made, and find out at least a little about the labour conditions they are made under. If it is a Canadian company and the labour conditions are poor, let’s shine a light on it, so pressure can be applied. We are educators. We can do this.

It’s a big issue and we (at FPSE) have our own issues we are making a priority this year. That doesn’t preclude us supporting organizations like CoDev more, though. Many times, when I make donations, I wonder where the money is being spent. Having seen first-hand the work CoDev does in Nicaragua and Honduras, if you have donation dollars you haven’t committed yet, I highly recommend supporting this worthwhile organization.

Respectfully submitted,

Leslie Molnar, 2nd VP